If You Love Something

by Brian

Published by Terror House Magazine

The first time I saw Maya she was laying on the train tracks on a clear blue summer afternoon.

“What are you doing?” I said, bringing my bicycle to rest alongside the tracks.

“Waiting for the train,” she said.

She didn’t move or look in my direction. Dark sunglasses covered her eyes, which I imagined to be blue.

Later, I would find out that they are green.

“I didn’t know the train ran here anymore,” I said.

“Well, it does. It’ll be here in about ten minutes,” she said.

She pulled a cigarette out of a pack on her stomach, lit up, and took a long drag. The smoke hung around her in the breezeless air. I got the sense my presence irritated her, so I continued biking down the tracks.

Right on time ten minutes later the train arrived with a deafening whistle. Its cars were packed with logs headed to the lumber mill downtown. The train smelled of metal and wood and industry.

As it whistled out of sight I rode back in the direction I’d come from. The girl was gone but there was a cigarette butt smoldering where she’d been lying.

“Shit, man, everything’s got a cost. Especially humanitarianism.”

The next time I saw her I was sitting on a picnic table along the river. She was wearing the same clothes as before: jean shorts and a black tank top that showed off heavily-tattooed arms.

She sat down at a table adjacent to mine, pulled out a cigarette, removed some of the tobacco, and stuffed in a bit of marijuana from a plastic wrapper. She replaced the tobacco and tried to light it, but the lighter wouldn’t light.

“Fuck,” she said in an exaggerated fashion, as if this was the final indignity in a string of them.

“Need a light?” I said.

She didn’t say anything but walked over to me. I studied her tattoos. There was a red-orange flower; jeweled skeletons; the striped legs and ruby shoes of the dead Wicked Witch of the West; a demonic-looking nymph.

I lit the cigarette for her.

“Thanks,” she said and walked away.

“Here, keep it,” I said. “You might need it again.”

She shrugged indifferently and accepted the lighter. I watched her stroll down the river trail nonchalantly smoking. She kicked off her sandals and carried them in her free hand as she walked in the thick grass.

There was something magnetically carefree about her. I had to know where she was going and what she was doing.

She walked like one of those kids in Family Circus, over picnic benches, swinging around poles, dipping down to the river banks and back up, stopping to lie in the grass or watch the river rush past in long gazes, climbing up into the cruck of a huge old cherry tree to smoke.

Her path led to a parking lot where the town let transients park their cars and RVs. The place was a subcommunity of bums, drifters, hobos, and tramps that had a reputation for danger. People were regularly murdered here.

She put her sandals back on, walked across the lot to an old minivan, and entered through the sliding door. Carefully, I edged along the lot trying to get a closer look.

The van had New Mexico plates, a tapestry of stickers on the back, and curtains covering the windows. Next to the van was a camping chair and a milk crate for a table, on top of which sat an ashtray made from the bottom of a soda bottle.

The van door opened and I ducked out of sight. She’d changed into sweatpants. She sat down on the camp chair and smoked.

A scruffy, good-looking man said something to her on the way back to his camper. The camper had a green and black camouflage paint job and no windows on the body.

She finished smoking and went inside the man’s camper. More than an hour later she came out and returned to her camp chair for a smoke. By then the sun was down and it was starting to get cool.

I rode past her once and circled back.

“I’ll bet you’re glad you kept that lighter,” I said.

“What?” she said.

“I gave you that lighter,” I said.

She looked at the lighter and then at me.

“Do you want it back?” she said.

“No, I…you’re homeless, aren’t you?”

“Hey, man, it’s unhoused, okay?” she said.

“Unhoused…yeah…I mean…you’re too pretty to be unhoused.”

I hadn’t meant to say these things. I only wanted to be close to her. Events seemed to be moving beyond my control.

She snickered. “I’ll tell them that the next time I’m at the shelter and they don’t have a room for me.”

“I’ve got a room,” I said.

She studied me more carefully.

“Look, man. I don’t know if you’re fucking with me, or if you’re some kind of sugar daddy. I’m not going to suck your dick, if that’s what you’re thinking.”

“You don’t have to…it’s free. The room’s empty. You could stay.”

“Shit, man, everything’s got a cost. Especially humanitarianism.”

“It’s just that…the room is empty. You could stay. For free.”

My complete lack of cool must have set her at ease because finally she said, “Show me.”

I unlocked the condo door and she stepped inside ahead of me.

“Go in the bathroom,” she said. “Lock yourself inside. That way I know you’re not gonna try to abduct me or something.”

I did as she said. I sat on the toilet and read a back issue of Scientific American. A few minutes later she knocked on the door.

“Yes?” I said.

“It’s nice,” she said. “Open the door.”

I remained sitting on the toilet.

“So, I can stay?” she said

“The room is empty,” I said.

“Like, tonight?” she said.

“Yes,” I said.

She brought a cot in from her van and set it up in the empty room. I provided her with fresh bedding and towels.

For dinner I made butternut squash soup, oven baked chicken, and salad. I knocked on the bedroom door. “Do you want dinner?” I said. “There’s plenty. Please, eat.”

She came out, helped herself, and took the food back to her room.

“What’s your name?” I said. “Mine’s Marcus.”

“Maya,” she said and closed the door.

I was up at 6:00. Maya’s door opened at 10:30 and I heard the toilet flush. She walked into the kitchen and stood there indecisively.

“Good morning,” I said. “Coffee? I can make breakfast, too.”

“I should get going,” she said. “Thanks for letting me stay.”

“You can stay longer,” I said. “The room’s empty.”

“Coffee cup?” she said after an uncomfortably long pause.

“Above the microwave.”

She poured a cup.

“There’s milk and half and half.”

“I like it black.”

She joined me in the living room and sat cross-legged on the carpet.

“So you don’t have a job or anything?” she said.

“I’m working right now,” I said. “I’m a computer programmer. But my passion is robotics.”

“Like, making robots?”

“Robotic components. I studied at MIT.”

I could tell by her face that this meant nothing to her. I liked this about her.

“Can I smoke?” she said.

“On the deck, please.”

“Got a light?”

“Look in the top draw there,” I said, pointing to a wheeled cabinet.

“You don’t smoke?” she said.

“No.”

“Then why do you carry around lighters?”

“I like to be prepared.”

She stayed outside on the deck for quite some time, sitting on the railing, chain smoking, and soaking up the sun. Her movements looked natural outside, whereas inside, she was like a stray dog brought in off the street, rigid and uncertain.

I wondered what the neighbors would think if they saw Maya. I’d never had a woman over to my place before.

“I’m running out to the store. Can I get you anything? Do you have dietary restrictions?”

“How about some Oh’s cereal?” she said. That was my favorite when I was a kid.”

I hadn’t heard of this brand of breakfast cereal, but I added it to my list.

“Help yourself to anything,” I said. “I’ll be back in a couple of hours.”

The division of mankind into the haves and have nots, the civilized and the uncivilized, the happy and the miserable, was a technical problem to be solved.

I stopped at the furniture store and ordered a bed to be delivered to the house. I also picked up some toiletries—toothbrush, toothpaste, mouthwash, lotion—since she didn’t seem to have any.

The condo was empty when I returned. Maya’s van was gone. I unpacked the groceries and sat down to finish some work. At around 4:30 there was a knock at the door. Maya was standing there. She could barely keep her eyes open.

“Come in,” I said. “I got the cereal you wanted.”

But she went straight to her room and didn’t come out for the rest of the day.

Later that afternoon while tidying up I noticed that my gold wristwatch was missing. I had no doubt Maya had stolen it and used it to purchase drugs. I’d read that addiction was rampant among the homeless.

The watch was immaterial. I could buy another one. It was far more important that Maya stay.

I stayed up late working on a robotics design. I had secured the intellectual property rights to a new type of circuit board that allowed “memories” to be stored much like a person’s. While prior generations of memory modules had served as glorified recording and playback devices, my design allowed a rich associative network to be created. This advancement would improve machine learning and allow robots to rely less on human inputs. More importantly, it would help to humanize robots in a way that was sorely lacking.

Shortly past midnight Maya emerged from her room and had a smoke on the deck. She appeared to have recovered from whatever she’d gotten into earlier. There was life in her eyes again.

She poured a giant bowl of cereal and stood crunching in the kitchen.

“Still working?” she said.

I explained the robotics circuit board to her.

“Aren’t robots going to waste us?” she said. “That’s what everybody’s saying.”

“I don’t believe so,” I said. “I think that robots can enhance human life.”

“What can robots do to us that’s worse than what we do to each other—or to ourselves?” she said.

I completely agreed. Machines, I believed, represented a promising new future for humanity. Evolutionary pressures had made man inevitably destructive. Coexisting was at odds with our biological imperatives, which made life a zero-sum game.

Robots, on the other hand, had only the pasts we gave them. They were not slaves to the determinism of competition, territorialism, tribalism, or predation.

Humans would never be a blank slate into which benevolence could be programmed, as so many naively believed. But robots were a tabula rasa.

I explained this excitedly to Maya.

“Tabula rasa?” she said.

“A clean slate. A chance to start over,” I said.

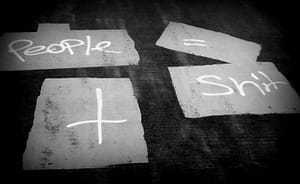

“You’re right,” she said. “People don’t change. They can’t change. Not really.”

It pleased me that we could connect on this fundamental point coming from completely different points of view. What I knew analytically, she knew intuitively.

Robotics, if they were to be a step forward for our kind, should synthesize these two human types. The animal in us had to be preserved for happiness’ sake, but for the sake of order, the instinctual must be regulated by the informed.

The division of mankind into the haves and have nots, the civilized and the uncivilized, the happy and the miserable, was a technical problem to be solved. Utopia could not be reached politically, but it was my belief that utopia could be engineered.

Inspired, I worked through the night and made several significant design modifications. Maya stayed up with me, sitting cross-legged on the floor quietly, arising at regular intervals to smoke on the deck. I found her to be a reassuring presence. Far from a charity case, Maya had helped me to reach new clarity in my work. I told her this and she seemed pleased.

Shortly after 5 a.m. I finished working. I’d been so engrossed that I’d forgotten to eat or drink. I poured myself a bowl of Oh’s cereal. Normally I avoided foods with added sugar, but I had to admit, the cereal was fantastic.

Maya’s bed arrived the next afternoon. The delivery man woke both of us up.

She squealed and gave me a hug when I told her I’d bought her a bed.

“It’s for the room,” I stressed, not wanting her to think I was too soft. “I’ve been meaning to put a bed in here for quite some time.”

This was a lie, however. The bed was for her and her alone.

I assembled the bed and laid down on the mattress. Maya laid down next to me. I yearned to reach over and take her in my arms. Her foot brushed against mine and I felt warm excitation. I pictured her laying on the train tracks the first time I saw her and my excitement grew.

In order to control the future, you have to control the past.

A good deal of research was being done on human companionship robots (crudely referred to as “sex bots”). One of the biggest challenges was developing a model that was more than an empty receptacle. Some progress had been made in this regard by programming in “turn-ons.” Men, however, and women especially, needed to feel desired.

Desire was based on memory. The tabula rasa had no memories—and thus no desires. If a companionship robot could be programmed with memories of a human lover, then its passion would be authentic.

This concept had broader implications as well. A robot could be programmed with memories in place of human evolutionary drives. Instead of embodying a brutal Darwinian struggle, a robot could contain impressions of a peaceful paradise of plenty, where all was provided and there was no deprivation or scarcity.

The religions of the world saw this as the image of heaven. But perhaps that future was only possible if we had memories of it. In order to control the future, you have to control the past.

That evening Maya asked if she could invite a friend over. I said it was alright, as long as they were quiet, because I had work to do.

It turned out her friend was the owner of the camper. I didn’t let on that I knew when she introduced him as “K-dawg.”

They went to Maya’s room and did not come out for several hours. I found it difficult to work knowing K-dawg was in there with Maya on the bed I had bought her. Whimpers of pleasure came from the bedroom and I put on headphones to drown out the sound.

I missed Maya sitting near me while I worked. I missed watching her smoke on the deck with her long, feline motions. I missed her simple way of giving life to my abstractions.

K-dawg left just before midnight. I heard the front door close and the ragged engine of his camper start up and pull away.

Maya came out for a cigarette then fixed herself a bowl of cereal. I had her to myself again, but it wasn’t the same. The ambiance was stained by the memory of K-dawg.

On Friday I left for a business trip to California. I was to meet with investors and designers in an attempt to secure production of a robot prototype that featured my circuit designs. I would be away from home for approximately a week and a half.

I told Maya she could stay if she wished. I gave her no special instructions. I knew she would do whatever she pleased. But that’s why I admired her. Reigning in her spirit would be unnatural, like putting a wild tiger in a zoo.

I hated Los Angeles with a passion. It was the saddest place I’d ever been to. The city was based on lies and subterfuge. Outwardly, the people were beautiful and happy. Inwardly, they were rotten and miserable.

But I could help them. My robot would make them happier. Through my robot they would be able to connect with another in a way that was no longer possible between two people. They had created this false world as a simulacrum of genuine human affection. But I could give them something realer.

The meeting with the investors went very well. They offered me the seed money I required to put my work into production. I left the office with a contract for $10 million in funding.

My circuitry design was the key to bridging the uncanny valley.

From there I traveled to Silicon Valley to meet with the principals of a leading robotics firm, one of whom I had studied with at MIT. I remained on their campus for the better part of a week working with them and their engineers. After some tense negotiations a deal was struck to be partners on a new companion robot. We would need to meet again to finalize a business plan, although most of the work could be done remotely.

As a final consideration I would receive the first prototype, designed to meticulous specifications that I provided for the robot’s memories and appearance. They assured me that the prototype would be 3D printed forthwith.

Due to breakthroughs in the field of cognitive science, creating memory was no more difficult than replacing a microchip in a circuit board. The altering of memories in humans was controversial and potentially dangerous. Laws had been passed to allow memory replacement only for certain serious medical conditions, and then only with the strictest oversight.

Robots, however, were not subject to these restrictions. While it’d been possible for many years to custom-program a robot with memories, the translation of these memories into action was clumsy at best. The robots were physically indistinguishable from humans, but their mechanical affectations gave them away. My circuitry design was the key to bridging the uncanny valley.

The financial implications of this breakthrough were astounding. I had no doubt that it would make me a very rich man. But money was not my primary motivation. I wanted to bring people happiness. They had suffered enough.

Arriving back at my condo I discovered that I’d been cleaned out. Electronics, furniture, artwork, kitchenware, tools, bicycles—all gone.

Stolen, I was sure, by Maya and K-dawg.

Maya’s cot was folded up where the bed used to be. Evidently she had left me a memento.

I unfolded the cot in the living room and sat down on the edge, looking around at the empty condo.

There was still a bit of food in the refrigerator as well as some coffee. I brewed a pot and made myself a sandwich.

I heard a truck outside. For a moment I thought it was K-dawg returning in his camper for whatever else he could get his hands on. There was a knock at the door. A UPS driver stood there, breathing heavily and supporting a large box. I signed for the parcel and he helped me carry it inside. The shipping label on the box said “Entercom Industries. Palo Alto, California.”

I removed the cardboard. Beneath was a thick layer of molded Styrofoam protecting the contents. I lifted off the top part of the foam and there she was. My creation.

She was the spitting image of Maya, right down to the jean shorts and black tank top and tattoos. I activated her by voice command. Her green eyes opened.

I asked her if she thought it was okay to take something wild and put it in a cage.

We made love on the living room floor and afterwards she went out on the deck for a cigarette. I watched her through the glass and thought about her as a wild tiger in a zoo.

A terrible sadness overcame me. Maya came running in and said, “Oh baby, what’s the matter?”

I asked her if she thought it was okay to take something wild and put it in a cage.

“Yes,” she said. “If you do it because you love the thing and want to care for it.”

She kissed me and I knew that she was right.

That night I sat on the cot working on my laptop and Maya sat cross-legged on the floor, keeping me company. We reminisced about our meeting and her moving into the condo. She told me what a good man I was for bringing her in off the streets. I had saved her, she said. She promised to love me forever.

I let her smoke in the house. I did not want her to be far from me. I didn’t care about the smoke, or the lack of furniture, or even continuing my work with Entercom.

None of that mattered. I had Maya now, and I was happy.